Osteoarthritis

Background

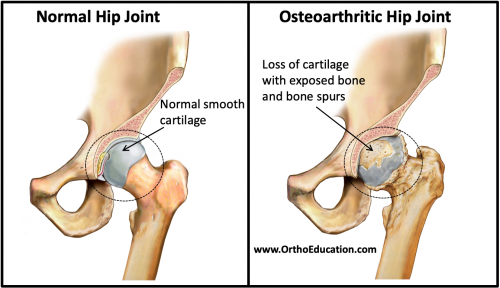

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis and affects millions of people throughout the world. Osteoarthritis is the loss of the smooth gliding cartilage that covers the end of the bones within a joint (Figure 1). It occurs when the hyaline cartilage, which is normally on the surface of the bones within the joint, begins to break down. In response to the cartilage breakdown, the cells in the cartilage start proliferating and release inflammatory agents. This causes the tissue lining the joint (the synovium) to proliferate and secrete an increased amount of joint fluid (synovial fluid). Patients therefore present with symptoms of joint swelling and inflammation due to cartilage loss.

Figure 1: Normal and Osteoarthritic Hip Joint

Clinical Presentation

Osteoarthritis can affect any joint, although it commonly affects joints in the fingers, hips, knees, and spine. Symptoms of osteoarthritis typically include joint pain, warmth, swelling, and restricted range of motion. Symptoms tend to worsen over time and with activity, but may temporarily improve with rest. Osteoarthritis occurs due to the loss of cartilage coving the joint, either from direct major trauma to the joint (ex. a fracture involving the joint), or from mechanical wear over time (ex. bow legs or knock knees causing knee osteoarthritis over time). This loss of cartilage causes the cells in the joint to secrete inflammatory mediators. Despite the inflammatory process and symptoms, osteoarthritis is often referred to as “non-inflammatory” arthritis.

Osteoarthritis is a chronic condition that worsens over time. Therefore, physical examination may be variable. The exam will often reveal joint swelling, localized joint discomfort, restricted joint motion, and sometimes painful crepitations (cracking) with joint motion. Bearing weight on the impacted joints often increases the pain. Patients also tend to have “start-up” pain -pain and stiffness after they have been sitting (or sleeping) in one spot for a period of time. This pain and stiffness often resolves after a few minutes of movement.

Risk Factors

- Traumatic injury to a joint

- Mechanical malalignment. Like a car tire that is put on in a crooked position and a joint that is maligned will tend to wear out the cartilage in the area of the joint that is subject to the excessive loading force. For example, bow-legged individuals tend to develop arthritis in the inside (medial side) of their knee joints.

- Advanced age: there is increased wear and tear on joints as people get older.

- Sex: women are at a higher risk of developing osteoarthritis.

- Hereditary predisposition. Some individuals increased risk of cartilage wear due to their genetics

- Obesity: obesity increases the amount of weight that is put on the joints of the lower body (i.e. hips, knees)

Imaging

X-ray

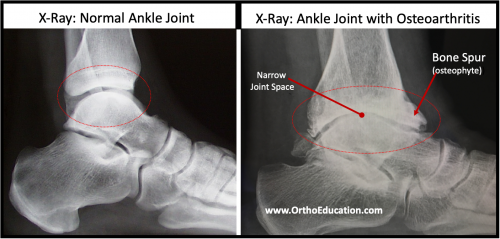

Classic findings of osteoarthritis on X-ray imaging (Figure 2) of affected joints include:

- joint space narrowing,

- bone spurs (osteophytes),

- subchondral cysts, and

- subchondral sclerosis.

Joint space narrowing occurs because osteoarthritis involves a loss/destruction of the cartilage within the joints. Subchondral cysts occur in osteoarthritis when increased fluid within the joint is forced through cracks in the bone at the joint surface allowing fluid-filled sacs to form inside the bone near the joint surface. Subchondral cysts, along with subchondral sclerosis, form on the surface of the bone that is just below the hyaline cartilage. Subchondral sclerosis is a thickening and hardening of the subchondral (“ beneath cartilage”) bone that form the joint. It can be identified as a bright white (more radiopaque) appearance along the edge of the bones within the joint. This thickening (sclerosis) occurs because breakdown of hyaline cartilage exposes the subchondral surface of the bone and causes the exposed bones in the joint to rub against each other. When the bone thickening occurs on the outer sides of the bones, as opposed to within the joint itself, bone spurs (osteophytes) form.

Figure 2: X-Rays showing Normal and Osteoarthritic Ankle Joint

Treatment

Lifestyle changes

- Weight loss directly reduces the weight put on the joints.

- Activity modifications (ex. limiting standing and walking) can decrease the amount that the joint is moved and the extent of force that the joint is exposed to.

- Relative immobilization of the joint with the use of a brace can help to protect the joint and decrease the resulting symptoms

- Strengthening muscles around the joint helps to protect the joint from excessive motion

Pain relievers

- Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs such as ibuprofen can decrease the pain associated with joint inflammation.

- Acetaminophen can also lessen the pain response.

- Cortisone injections may also be administered within the affected joint. These intraarticular (within the joint cavity) injections are often used to decrease pain.

Surgery

- Arthroplasty (joint replacement) may be indicated in some cases. This procedure involves replacing the damaged parts of the joints with either metal or plastic that serve a similar purpose.

- Joint fusion is often used as a surgical treatment of severe osteoarthritis in certain joints (ex. ankle and foot). This procedure is designed to convert a painful stiff joint into a painless stiff joint.